(Disclaimer: some of the things you’ll read here might be too graphic for you. Also, this story is 100% factual, however I did put a little bit of creative spin to it so it doesn’t look too bland. Enjoy)

Christa Gail Pike came into the world on March 10, 1976, in a small town in West Virginia. From the very beginning, her life was unsteady. Her mother, Carissa Hansen, was a very wild and reckless young woman.

Some people who knew the family said Carissa might have used drugs or drank too much, though no one could prove it for sure. Christa’s father, Glenn Pike, was barely a part of her life. He and Carissa split up when Christa was still little, and he faded away, leaving her with a mom who couldn’t hold things together.

Christa spent most of her childhood moving around, especially in Durham, North Carolina. Carissa had boyfriends who came and went, and each one seemed to make life harder.

Sometimes they had a place to stay, sometimes they didn’t. Christa went to school when she could, but it wasn’t steady. Kids who grew up with her remembered a girl who could be fun and smart one minute, then furious the next. She’d lash out over small things, like someone taking her pencil or looking at her wrong.

Her mom didn’t step in to help much. Carissa was too caught up in her own problems, leaving Christa to deal with everything alone. Neighbors said they’d see her wandering the streets as a little girl, looking lost but too stubborn to ask for help.

One of the biggest blows came when Christa was nine years old. Her grandmother, her mom’s mom, passed away suddenly. This grandmother was special. She lived nearby and would take Christa in when things got bad at home.

She’d cook her meals, brush her hair, and tell her stories, giving Christa a taste of what love felt like. When she died, it was like a light went out. Christa didn’t cry in front of people, but those close to her said she got quiet for a while, then meaner than ever.

She started picking fights at school and breaking rules, like she didn’t care anymore. Her grades dropped, and teachers noticed she’d sit by herself, staring out the window instead of listening.

There were whispers about worse things too. When Christa got older and talked to doctors or lawyers, she hinted that people had hurt her as a kid. She said her mom’s boyfriends might have hit her, or maybe done things that were even more awful.

She didn’t give clear stories, and no one found proof, like police reports or hospital visits. But the idea stuck with some people who studied her later. They thought it could explain why she was so full of rage.

Whether it happened or not, Christa grew up fast and hard. By 13, she was skipping school all the time, smoking cigarettes she stole, and hanging out with older kids who got into trouble. She got caught shoplifting once, taking candy and cheap jewelry from a store, but the police just sent her home since she was so young.

By her mid-teens, Christa started leaving home for days, staying with friends or crashing wherever she could. Then, at 18, someone suggested Job Corps, a program where she could learn a skill and maybe turn things around.

She signed up and moved to Knoxville, Tennessee, in late 1994 to train as a nurse’s aide. It was supposed to be her big chance. The program gave her a bed, food, and classes, but Christa couldn’t shake who she’d become.

She argued with teachers, ignored rules, and found two people who’d follow her anywhere: Tadaryl Shipp, a 17-year-old with his own wild streak, and Shadolla Peterson, a quiet girl who stuck close to Christa.

In January 1995, Christa Pike’s life spun out of control. She was 18, living at the Job Corps center in Knoxville, Tennessee, and obsessed with her boyfriend, Tadaryl Shipp. He was 17, a skinny guy with a wild side, and they were always together, sneaking off to smoke or mess around.

But Christa thought another girl, Colleen Slemmer, was getting too close to him. Colleen was 19, quiet, and just trying to get by in the program. Christa didn’t care. She was sure Colleen wanted Tadaryl, even though friends said Colleen barely talked to him. Christa’s jealousy grew into paranoia. She’d stare at Colleen, whisper threats, and tell people she’d make her pay.

On January 11, 1995, Christa decided to do just that. She got Tadaryl and their friend Shadolla Peterson, an 18-year-old who stuck to Christa like glue, to help her. She told them she wanted to scare Colleen and show her who was boss. They worked out a plan to trick Colleen into leaving the dorms.

The next day, January 12, Christa found Colleen and played nice. She smiled and said they should hang out, maybe smoke some weed, and fix their problems. Colleen didn’t suspect a thing. She agreed, thinking it was a peace offering.

That night, around 8 p.m., the four of them left the Job Corps building and walked to a lonely spot Christa had chosen: an old steam plant near the University of Tennessee’s agriculture campus. It was dark, hidden by trees, and silent, perfect for what Christa had in mind.

For a little while, they walked together, and Colleen thought it was just a casual night. But when they reached the steam plant, Christa’s act dropped. She turned on Colleen, yelling that she’d been after Tadaryl.

Colleen tried to explain, saying it wasn’t true, but Christa was past listening. She pulled a box cutter from her pocket, and the fight started. Colleen raised her arms to block, but Christa slashed at her, cutting deep into her skin. Christa lunged, grabbed her by the hair, and slammed her to the ground.

Christa punched Colleen’s face hard, splitting her lip. She kicked her in the stomach and ribs while Colleen curled up, gasping. Tadaryl stepped in, swinging his fists too, busting Colleen’s nose until blood poured out.

They tied her hands with some rope they’d brought, knotting it tight so she couldn’t hit back. Colleen’s screams turned to whimpers as Christa took the box cutter and sliced a pentagram into her chest, carving slow and deep. Blood welled up, soaking Colleen’s shirt, and she cried out in pain. Christa smiled, saying it was her mark.

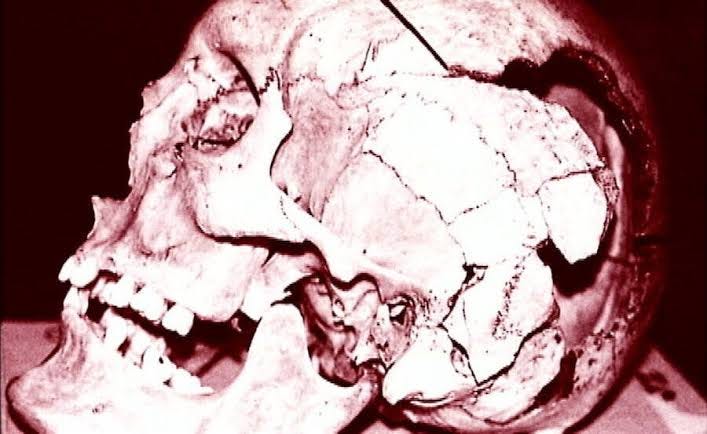

But that wasn’t enough. Christa grabbed a heavy piece of asphalt, a jagged chunk of old road about the size of a brick. She raised it high and smashed it down on Colleen’s head. The first hit cracked her skull, blood splattering onto the ground.

Colleen twitched, still alive, so Christa hit her again, then again, caving in the side of her head. Colleen’s face was a mess, one eye swollen shut, the other staring blank. Even after she stopped moving, Christa kept going.

She took a small knife and dug into Colleen’s shattered skull, prying out a bloody piece of bone, about an inch wide. She held it up, grinning, and stuffed it in her pocket as a prize. Tadaryl kicked the body a few times, and Shadolla just stood there, pale and quiet, letting Christa lead.

When it was over, Colleen lay dead in a heap, surrounded by trash and leaves. Her head was smashed open, blood pooling under her, and her chest was a carved-up ruin.

It was after 10 p.m. when Christa, Tadaryl, and Shadolla headed back to the dorms. Christa wiped blood off her hands and acted like nothing big happened. She hid the skull piece in her jacket and later showed it to a friend, laughing about how she’d “fixed” Colleen. The next morning, January 13, a worker found the body.

(Colleen’s fractured skull)

Colleen’s face was unrecognizable, her skull split, and her clothes stiff with dried blood. Police got involved fast. Christa bragged to people at Job Corps, saying she’d killed someone who crossed her. By January 14, she, Tadaryl, and Shadolla were arrested.

Tadaryl Darnell Shipp was 17 years old when he helped Christa kill Colleen. Born on April 7, 1977, in Memphis, Tennessee, he grew up in a gritty part of the city where money was scarce and trouble was easy to find.

He was tall for his age, about six feet, with a lanky build and dark eyes that didn’t give much away. He had a quiet way about him, not loud or pushy, but he could flip a switch and get mean if someone crossed him.

Friends from Memphis said he liked to draw, sketching cars and dragons in notebooks, but he’d rip the pages up if anyone saw. By 17, he’d dropped out of high school and was drifting.

That’s when his mom or maybe a counselor signed him up for Job Corps in Knoxville, hoping he’d learn a trade like carpentry or mechanics and stay out of trouble. He got there in late 1994, and within weeks, he met Christa Pike.

Christa and Tadaryl hit it off right away. She was wild and loud, always talking about big ideas, and he liked how she didn’t care what anyone thought. They’d sit together in the dorm common room, sharing cigarettes she’d snuck in, or slip outside to kiss in the dark.

Christa called him “Tad” and said he was hers, like they were meant to be. Tadaryl didn’t talk as much, but he’d nod and smile, letting her lead. People at Job Corps noticed how he followed her everywhere, like a shadow. They’d skip classes together, smoke in the woods, and whisper about getting out of Knoxville someday.

When Christa got jealous about Colleen Slemmer, Tadaryl listened. She’d rant about how Colleen was after him, even though Colleen was just a friendly girl who said hi sometimes. Tadaryl didn’t argue; he went along.

Shadolla Peterson, the third member of the gang was 18, born in Knoxville, Tennessee, on June 15, 1976. She grew up just a few miles from where the murder happened. Her family wasn’t rich or poor, just getting by.

Her dad worked at a factory, and her mom stayed home with Shadolla and her two younger brothers. She didn’t talk much, even as a kid. At school, she kept to herself, doodling in the margins of her homework instead of raising her hand.

She wasn’t dumb, but she didn’t try hard either, barely passing her classes. By high school, she’d stopped caring and dropped out at 16. She worked odd jobs, like bagging groceries, before her parents pushed her into Job Corps in 1994 to learn something simple, maybe housekeeping or kitchen work.

Shadolla met Christa soon after arriving in Knoxville. Christa was loud and bossy, everything Shadolla wasn’t, and Shadolla latched on. She’d follow Christa around the dorms, laughing at her jokes and nodding at her stories.

They weren’t best friends, but Shadolla acted like they were. She’d carry Christa’s books or save her a seat, happy to be noticed. When Christa started dating Tadaryl, Shadolla stuck around, the third wheel who didn’t mind.

She didn’t care about Colleen Slemmer one way or the other, but when Christa got mad about her, Shadolla listened. On January 11, 1995, Christa told her and Tadaryl she wanted to teach Colleen a lesson. Shadolla didn’t argue or ask why; she just said okay.

On January 12, Shadolla went with them to the steam plant. She wore a faded jacket and kept her hands in her pockets as they walked Colleen there. When Christa attacked, Shadolla didn’t jump in like Tadaryl.

When Christa bashed Colleen’s head with the asphalt, over and over, until her skull split open and brain oozed out, Shadolla stayed still. She didn’t hit or kick, but she didn’t run or yell for help either.

Police arrested Shadolla on January 14, 1995, after Christa bragged about the murder. At her trial in 1996, the story came out differently for her. Witnesses said she was there but didn’t hit Colleen.

Her lawyer argued she was too meek to stop Christa, just a scared kid who got swept up. The prosecution said she could’ve run for help but didn’t, making her part of it. In a deal to avoid a murder charge, Shadolla pleaded guilty to aiding and abetting—helping the crime happen.

On April 10, 1996, she got six years of probation, no jail time, because she was young and didn’t touch Colleen. She went back to Knoxville, living quietly with her family. By 2002, her probation ended, and she faded away. No one knows much about her now—some say she got married, others think she’s still in Tennessee, working a low-key job.

Everything comes crashing

The evidence against Christa was ginormous. First, there was her confession. On January 14, 1995, after her arrest, she sat in a police station interrogation room. She’d been picked up that morning, still wearing the same clothes from the night before, her jeans speckled with dried blood and her hands shaky from no sleep.

Two detectives were with her: Randy York, a gruff man in his 50s with a buzz cut and a notepad, and Amy McCartt, a younger woman with sharp eyes and a tape recorder. They’d heard whispers from Job Corps kids about Christa bragging, so they brought her in fast.

Her voice stayed flat as she narrated everything in detail, like she was reading a grocery list. She said she pulled out a box cutter, a cheap one with a yellow handle she’d bought at a hardware store, and slashed Colleen’s arms when they got to the steam plant.

She admitted yelling at her, accusing her of chasing Tadaryl, even though Colleen swore she wasn’t. Christa told them she threw Colleen down, cut a pentagram into her chest with the box cutter, and watched the blood run out in thick lines.

She said Colleen screamed and begged, but she didn’t stop. Then she described picking up a piece of asphalt, a heavy, rough chunk about the size of two fists, and smashing it into Colleen’s head—not once, but over and over, maybe 10 or 12 times.

She said she felt the skull give way, heard it crack like a dry branch, and saw blood splash onto her shoes. She even told them about taking a piece of the skull, a small, jagged bit with hair stuck to it, because she “wanted something to remember it by.”

Next was the skull fragment. Police searched Christa’s dorm room on January 15, flipping her mattress and digging through her stuff. In the pocket of her black leather jacket, stuffed in a corner of her closet, they found it: a piece of Colleen’s skull, about an inch wide and half an inch thick, crusted with dried blood and a few strands of dark hair.

There was more too. The box cutter turned up near the steam plant on January 13, half-buried in mud about 20 feet from Colleen’s body. Its blade was bent and coated in dried blood that matched Colleen’s DNA. Each piece of evidence screamed guilt, and Christa’s own words tied it all together.

Christa’s Trial

The trial started on March 22, 1996, in Knox County Criminal Court. The room was packed every day, with reporters scribbling notes, Colleen’s family sitting red-eyed in the front row, and curious locals filling the benches.

Christa walked in wearing an orange jail jumpsuit, her dark hair pulled back tight. She was small, barely five feet tall, and looked younger than 20, but her face was hard, like she’d already given up.

Her lawyers, two public defenders named Bill Talman and Julie Ann Rice, sat beside her, whispering to her as the judge, a stern man named Richard Baumgartner, banged his gavel to start.

The prosecutor, William Crabtree, was a big guy with a deep voice who didn’t hold back. He stood up and told the jury—a mix of 12 men and women, mostly middle-aged—that Christa wasn’t just a killer, but a monster.

He said she planned the murder, enjoyed it, and bragged about it. Crabtree painted a picture of that night at the steam plant, step by step, making the jury wince. Christa’s lawyers fought back. They said she was a messed-up kid, barely an adult, with a brain full of problems from a bad life. They begged the jury to see her as human, not evil, and asked for mercy.

Witnesses came one after another. A Job Corps student named Kim Iloilo, a nervous girl with glasses, said she saw Christa the day after the murder, January 13.

Kim testified that Christa showed her a piece of Colleen’s skull, a jagged, bloody chunk about an inch wide, and laughed, saying, “I bashed her head in good.” Kim cried on the stand, shaking as she spoke.

Another student, a guy named Brian Jones, said Christa told him she’d “taken care of” Colleen because she was after Tadaryl. He said Christa seemed proud, not sorry. Tadaryl Shipp and Shadolla Peterson didn’t testify, they had their own trials, but their statements to police were read out loud. Tadaryl admitted hitting Colleen, and Shadolla said she watched Christa do it all.

Christa’s mom, Carissa Hansen, took the stand too. She told the jury about Christa’s rough childhood—moving all the time, losing her grandma, maybe getting hurt by men in their house. Carissa said she wasn’t a good mom, but she begged them not to kill her daughter.

The jury listened, some taking notes, others staring at Christa, who wouldn’t look up. Then Christa herself spoke. She didn’t deny the murder, but she said it wasn’t planned like the prosecutor claimed. She told them she “lost it” that night.

When Crabtree asked why she kept the skull piece, she shrugged and said, “I don’t know.” The room went silent.

The trial lasted a week, ending on March 29, 1996. The jury took just two hours to decide: guilty of first-degree murder and conspiracy to commit murder. Then came the penalty phase—life in prison or death. Crabtree pushed for death, saying Christa’s crime was “heinous, atrocious, and cruel,” words the law used for the worst cases.

Her lawyers pleaded for life, bringing a doctor who said Christa had mental problems, like borderline personality disorder, from years of pain. The jury went back out and came back on March 30 with their answer: death by lethal injection.

Christa didn’t cry or yell; she just sat there as Judge Baumgartner read the sentence. Colleen’s mom, May Martinez, sobbed in the front row, clutching a picture of her daughter.

The courtroom erupted—Colleen’s family cried and hugged, while Christa’s mom, Carissa, slumped in her seat, wailing. The next day, papers like the Knoxville News Sentinel ran front-page stories: “Teen Killer Gets Death” and “Youngest Woman on Death Row.” People couldn’t stop talking about it.

In Knoxville, some saw it as a win, others hated the verdict. On April 1, a crowd of 70 or so marched at the University of Tennessee, mostly students and a few professors, chanting “Life, Not Death.”

They carried banners reading “18 Isn’t Enough” and “Stop Killing Kids.” A junior named Emily Harper told a local TV station, “She’s my age, messed up from a bad life. We don’t fix this by killing her.” A church group from First Baptist Knoxville joined in, led by Pastor James Reed, who preached to about 100 people that Sunday, saying, “Christa’s soul can still be saved.

Let her live and repent.” Letters flooded in, some calling her a victim of a broken system, others begging Governor Don Sundquist to step in. He didn’t.

Christa was the youngest woman in modern U.S. history to get death, and lawyers everywhere took note. Her defense filed an appeal on April 5, 1996, saying the jury ignored her mental health—doctors had found depression, personality disorders, and possible brain damage from her childhood.

They argued the confession was shaky, taken after hours of questioning with no lawyer, when Christa was exhausted and scared. Judge Baumgartner shot it down, but the fight went higher.

In 1998, the Tennessee Court of Criminal Appeals heard the case. Christa’s team brought Dr. Jonathan Pincus, a brain expert, who showed scans and said her frontal lobe, the part that controls impulses was off, likely from years of stress or abuse.

Prosecutor Crabtree countered with her confession and the skull, saying she knew exactly what she did. The court ruled against her in 1999, with Judge Gary Wade writing, “Her youth doesn’t erase the torture she inflicted.”

The Tennessee Supreme Court took it up in 2001, and again, Christa lost. Her lawyers kept swinging new appeals in 2006, 2010, 2015; each time claiming fresh angles, like unfair jury picks or evolving laws.

In 2005, the U.S. Supreme Court’s Roper v. Simmons decision banned death for under-18s, and Christa’s team argued she was close enough at 18 years, 10 months. Courts said no, she was over the line.

Life on the inside

Christa Pike walked onto Tennessee’s death row on March 30, 1996, after her sentencing. She was sent to the Tennessee Prison for Women in Nashville, the only woman among a handful of death row inmates in the state.

Christa didn’t settle into prison life easy. On August 24, 2001, five years into her sentence, she tried to kill another inmate, a woman named Patricia Jones.

Patricia was 32, a lifer locked up for stabbing her boyfriend in a drunken fight. She and Christa shared the death row unit. Patricia and Christa didn’t get along. Guards later said Patricia teased Christa, calling her “Skull Girl” because of the Colleen Slemmer murder, and bragged she’d never be scared of a “little thing” like her.

That day, around 2 p.m., the women were let out of their cells for rec time. The dayroom had a guard, Officer Tammy Lewis, watching from a glass booth, but she was writing reports, her eyes down.

Christa sat at a table, picking at her nails, while Patricia played cards with two others, laughing loud. Something snapped. Witnesses said Patricia made a crack about Tadaryl Shipp, maybe saying Christa couldn’t keep a man even in prison.

Christa stood up, her face red, and walked over. She didn’t say a word. She grabbed a shoelace she’d slipped off her sneaker, a thick white one she’d been hiding, and lunged at Patricia from behind.

Christa wrapped the lace around Patricia’s neck, yanking it tight with both hands. She thrashed, knocking over the table. Officer Lewis looked up, dropped her pen, and hit an alarm. It took 20 seconds—maybe 30—for two more guards to rush in.

The prison locked Christa down after that. She got a new charge: attempted murder. On January 15, 2002, she faced a quick trial in Davidson County. Patricia testified. Christa’s lawyer said she snapped under stress, not planning it. The jury didn’t care. They found her guilty in an hour, adding 25 years to her sentence, though it didn’t mean much with death already on the table.

Guards moved her to a tighter cell, a 6-by-8-foot box with a steel door, and cut her dayroom time. She told a prison shrink later, “Patricia had it coming,” showing no regret.

Escape plot

In 2004, she hatched a plan to break out, nine years into her sentence. She’d made a friend, sort of—a guard named Justin Heflin. Heflin worked the death row night shift.

Christa started talking to him through her cell door, small stuff at first—complaining about cold food or asking about his day. Heflin soon fell for her, slipping her extra snacks like candy bars or a soda now and then, against the rules.

By spring 2004, Christa had a bigger ask. She told Heflin she wanted out, saying she’d die in there if he didn’t help. On June 10, 2004, another inmate, a woman serving life for robbery, overheard Christa whispering to Heflin during a cell check. She snitched, trading the tip for a phone call to her kid.

Prison brass set a trap. They let Heflin think he was clear, watching him close. He’d planned to sneak her out at 3 a.m., through a back exit by the laundry room, where a buddy with a car would wait. But guards were ready.

They grabbed him at midnight, before he reached her cell, and searched the bag. Heflin broke down crying, saying Christa “made him do it.” She denied it, claiming he was obsessed with her.

Heflin got fired and charged with aiding an escape attempt. On September 20, 2004, he pleaded guilty and took two years in prison, serving 18 months before parole. Christa faced a disciplinary hearing, not a full trial, since it was inside prison rules.

On July 1, 2004, a board of three officers—led by Warden Carla Dixon—added stricter rules: no visitors for six months, no mail except legal stuff, and 23-hour lockdown daily.

In 2015, at 39, Christa fought back. With a new lawyer, a fiery woman named Kelly Gleason from the Federal Public Defender’s Office, Christa sued Tennessee’s prison system.

Filed on March 10, 2015, in U.S. District Court, the lawsuit claimed solitary was “cruel and unusual punishment,” banned by the Constitution’s Eighth Amendment. Gleason argued Christa had been in isolation for over 15 years straight—5,475 days by then—with no end, wrecking her mind.

The state fought hard. Lawyers for Tennessee, led by a prosecutor named Herbert Slatery, said Christa earned her isolation with her “violent history.” They pointed to the 2001 strangling and 2004 escape plot, saying she was too dangerous for less.

On June 22, 2017, Judge Travis McDonough ruled against Christa, saying her treatment was tough but legal, since death row was meant to be strict. Her team appealed to the Sixth Circuit Court in 2018, losing again on October 3, 2019, when Judge Alice Batchelder wrote, “Her crimes justify her conditions.”

Christa tried one more time. In 2022, with Gleason still pushing, she filed a new claim tied to a 2021 Supreme Court case, Dunn v. Ray, about prisoner rights. She said 25 years in solitary—9,125 days by then—violated new standards, especially as a woman with mental health issues.

A hearing on April 15, 2023, brought fresh hope. A guard, Officer Lena Brooks, testified she’d seen Christa bang her head on the wall, crying for hours, and worried she’d die before execution. But on January 10, 2024, Judge Curtis Collier denied it, saying her sentence trumped her complaints.

As of March 24, 2025, she’s still in that cell, her appeals exhausted, her execution date creeping closer, rumored for late 2025 or 2026.

What do you think? Is Christa an inherently bad person or is her childhood to blame?

Why’d ya make me read this? Ruined my whole morning.

I have been a forensic psychiatrist for 28+ years, and I believe we have learned a powerful lesson in purposely segregating human beings for grossly long periods of time: it is cruel & inhumane. Period. I would frequently visit Death Row, and even the most heinous of criminals can be managed appropriately without segregating them in total isolation without some form of human interaction. Even the most psychopathic - who, by far, are the most dangerous of individuals that can be encountered by correctional custody staff - can be properly managed without exposing them to other inmates, with proper training and protocol. This death row inmate woman never should have had physical access to other inmates for any reason, and her "escape" plan would never have happened - literally would never have begun or materialized - in a properly vetted and properly trained custody staff, working in a maximized facility, where a protocol does not allow for a single "observer" to be distracted for even a moment, and then allows 30-seconds to elapse before officers will arrive to assist. When inmates know that such behavior will not be tolerated by a well trained team; they actually witness the professional response of a well-trained team; see the predictability of a well-trained team as, for example, an execution date draws near; and most importantly, mental health professionals and spiritual advisors are available throughout the course of incarceration leading to execution, changes in behavior can often be dramatic. If you are unwilling to show respect and dignity for another human being, minimally, you will be continually fighting for compliance.